Startup Option value calculator

Have you ever wondered about the value of the options and shares that startups issue to employees? If you ask the startup

CEO, she tells you they are winning lottery tickets. If you ask your grandmother, she tells you they are worthless. If you use

this calculator, you will get a better answer.

This calculator was developed by Will Gornall at UBC and Ilya

Strebulaev at Stanford University using methodology similar to their paper

Squaring Venture Capital Valuations with

Reality. This is a beta version, come back soon for updates. By accessing or using the site, you are accepting our terms of use.

Other considerations

This calculator values shares from the perspective of a diversified investor. The value of these shares to YOU may be

substantially lower.

Can you tolerate risk?

Startup options are very risky, as illustrated by the dice roll example above. The more money you have and the more secure

your job is, the better you are able to deal with that risk. Beyond that, some people are more worried about risk than

others.

The less you are able to deal with risk, the less your shares are worth to you.

Are you impatient?

If you have high interest debt or need to buy a house, you may prioritize money today. That reduces the value of payoffs

that will come years from now.

The more you need money today or in a few years, the less your shares are worth.

Will you quit?

If you leave a startup, you lose your unvested ownership. Vested ownership may also lose value as you may have to exercise

options (creating tax and cash-flow issues) or be forced to sell them to the company.

The more likely you are to leave the company early, the less your shares are worth.

Will you need to sell?

Selling shares in startups can be hard. First, startups have a variety of contractual rights that make it hard for employees

to sell their shares to outsiders. Second, buyers may know less about the startup than employees will be worried the company is

a

lemon - if the company was great, why would you sell? Third,

the platforms that facilitate share sales, such as EquityZen and SharesPost charge a sizeable commission.

If you need to sell ownership in startup, you may get less than the fair value.

What is your tax situation?

Receiving, exercising, or selling stock options or shares can create complicated tax situations. You should consult with a

tax advisor in order to avoid an unwanted tax surprise. Your tax bill may end up being between 15% to 50% of the proceeds.

Plan for taxes and talk to a tax advisor.

Are the model assumptions correct?

This model uses parameter assumptions that are appropriate for the average VC-backed company. These assumptions were

designed to be appropriate for the typical such company. If your company has definite plans to go public in the next year, it

is likely no longer typical (you may want to reduce the "Avg. time until exit" to 2 years in such a case). Similarly,

if your company has just had a recap or significant down round, it is not typical. In either case, these special considerations

prevent our off-the-shelf model from reflecting your company's reality unless you customize the parameter assumptions.

If your company is atypical, the values produced may be incorrect.

Is the preloaded financial data correct?

To help startup employees who do not have access to financial data, the calculator allows the easy loading of startup

financial data gathered from legal filings. Checking these data for accuracy for all startups is extremely labor intensive. In

addition, some companies enter into very complicated contracts with its investors that require more intricate modeling. Because

of this some startup financial information may be incorrect.

The financial data we have preloaded is a work in progress and may contain errors.

How does it work?

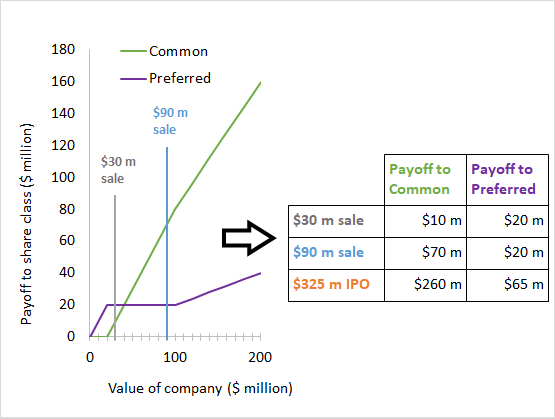

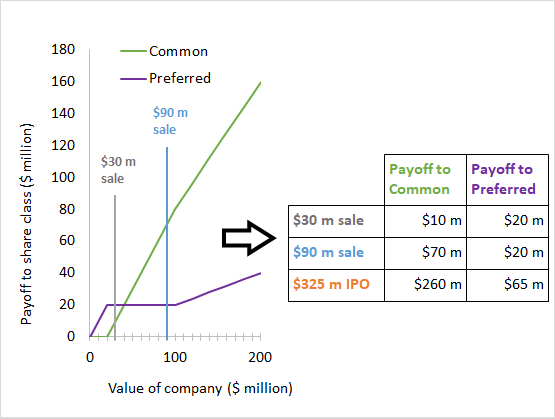

Step 1 The program guesses the value of the company. Based on that value, it projects out many potential exits.

Step 2 For each possible exit, the program finds the payoff to each class of share.

Step 3 Based on these exits, the program values each security.

Step 4 The program sets the value of the company so that the most recent VC round is fairly priced. That company value

is then divided between options, common shares, and preferred shares.

Refer to our paper

Squaring Venture Capital Valuations

with Reality for full details of the valuation process.

About the authors

WILL GORNALL

Assistant Professor of Finance, University of British Columbia

will.gornall@sauder.ubc.ca

willgornall.com

Will Gornall is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the University of British Columbia. He is an expert on venture

capital and innovation financing.

ILYA A. STREBULAEV

The David S. Lobel Professor of Private Equity, Graduate School of Business, Stanford University

istrebulaev@stanford.edu

https://ilyas1.people.stanford.edu/

Ilya A. Strebulaev is the David S. Lobel Professor of Private Equity and Professor of Finance at the Stanford Graduate

School of Business, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He is an expert in corporate finance,

venture capital, innovation financing, and financial decision-making. He is the faculty director of the Stanford GSB Venture

Capital Initiative.

Our venture capital papers

We develop a valuation model for venture capital--backed companies and apply it to 135 US unicorns, that is, private

companies with reported valuations above $1 billion. We value unicorns using financial terms from legal filings and find that

reported unicorn post--money valuations average 48% above fair value, with 14 being more than 100% above. Reported valuations

assume that all shares are as valuable as the most recently issued preferred shares. We calculate values for each share class,

which yields lower valuations because most unicorns gave recent investors major protections such as initial public offering

(IPO) return guarantees (15%), vetoes over down-IPOs (24%), or seniority to all other investors (30%). Common shares lack all

such protections and are 56% overvalued. After adjusting for these valuation-inflating terms, almost one-half (65 out of 135)

of unicorns lose their unicorn status.

We survey 885 institutional venture capitalists (VCs) at 681 firms to learn how they make decisions across eight areas: deal

sourcing; investment decisions; valuation; deal structure; post-investment value-added; exits; internal organization of firms;

and relationships with limited partners. In selecting investments, VCs see the management team as more important than business

related characteristics such as product or technology. They also attribute more of the likelihood of ultimate investment

success or failure to the team than to the business. While deal sourcing, deal selection, and post-investment value-added all

contribute to value creation, the VCs rate deal selection as the most important of the three. We also explore (and find)

differences in practices across industry, stage, geography and past success. We compare our results to those for CFOs (Graham

and Harvey 2001) and private equity investors (Gompers, Kaplan and Mukharlyamov forthcoming).

We study gender and race in high-impact entrepreneurship using a tightly controlled randomized field experiment. We sent out 80,000 pitch emails introducing promising but fictitious start-ups to 28,000 venture capitalists and angels. Each email was sent by a fictitious entrepreneur with a randomly selected gender (male or female) and race (Asian or White). Female entrepreneurs received a 9% higher rate of interested replies than male entrepreneurs pitching identical projects and Asian entrepreneurs received a 6% higher rate than their White counterparts. Our results suggest that investors do not discriminate against female or Asian entrepreneurs when evaluating unsolicited pitch emails.